HARPER'S NEW MONTHLY MAGAZINE.

Vol. ?

New York City, August, 1865.

No. CLXXXIII.

[317]

NEVADA.

_________

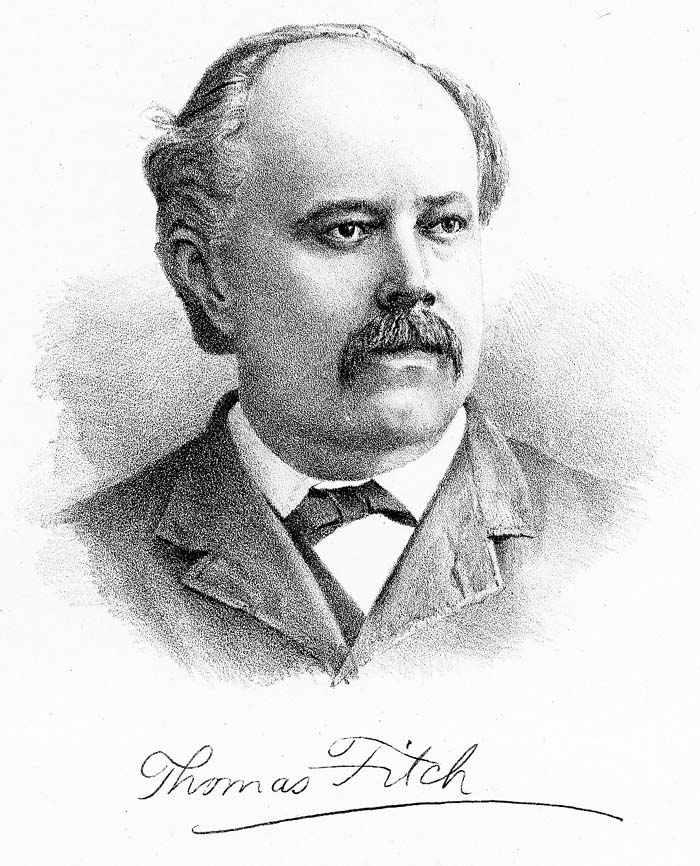

(by Tom Fitch)

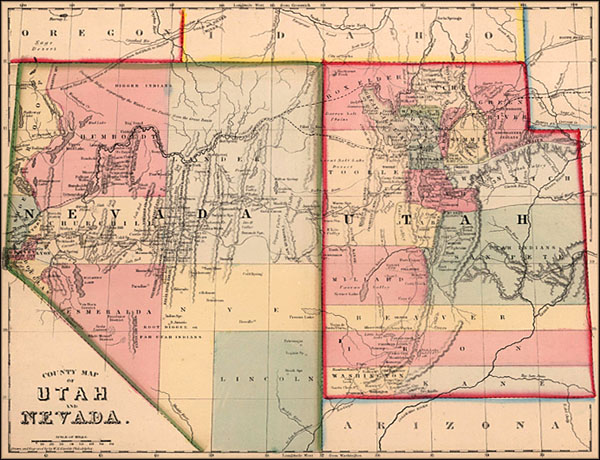

Carry yourself in imagination far from the centres of civilization, over weird wastes and savage wilds, to a point where the 116th degree of west longitude intersects the

42d degree of north latitude. The head-waters of the Owyhee -- there a small river or brook -- are gurgling a mile or so behind you; your right foot presses the golden sands

of Idaho; your left is under the spiritual jurisdiction of Brigham Young; while at your feet the unerring eye of science marks out the northeastern corner of the new State of

Nevada. Travel thence due west for a hundred miles, over rugged mountains, lofty buttes, and patches of desert and valley, and you reach the Mica Hills, glittering in the

sunlight like cones of gold; thirty miles more in the same direction will bring you to the divide between the waters of the Columbia River and the Great Basin; a hundred

miles more still due west, and you are in a wondrous country of petrified trees -- stony finger-points of the antediluvian past -- of sparkling streams, translucent lakes, high

mountains, and gloomy cañons. Then you have a range of granite mountains to cross, and forty or fifty miles more carries you to the northeastern corner of our young State,

where, in the vicinity of Nye's Lake and Roop's Lake, 7000 feet above the sea, 250 miles from the initial point, and where the 120th line of west longitude crosses the 42d

parallel of north latitude, the State of Oregon stretches to the north, and Lassen County, California, faces you on the west. Southward thence along the 120th longitudinal

line, with California on your right, and Nevada on your left, pursue your course. You will need the wing of an eagle and the eye of a bee to follow this line. The sombre

Sierras, crowned with tresses of pine, frowning with battlements of barren rock, wrinkled with mighty cañons, and set with a tiara of glittering lakes, will be your companion

for hundreds of miles. You skirt the western border of Honey Lake, and pass over the centre of the inland sea of the Sierras -- Lake Bigler, or, as it is now called, Lake

Tahoe, from the Pahutah designation of Big Water. About thirty miles from the northern end of this lake, some ten miles from the eastern shore, at a point where the 120th

line of west longitude intersects the 39th parallel of north latitude, the boundary line strikes off in a southeasterly direction, at an angle of about 45 degrees, following the

sweep of the Sierras for 200 miles to a point where the 37th parallel of north latitude intersects the 117th line of west longitude. Thence across a region seldom or never

trodden by the foot of man; along the line of desolate Arizona, with the burning sands of the distant Colorado heating the air to intensity -- sixty miles -- to the spot where

the southwestern corner of Nevada joins Utah and Arizona; thence 300 miles due north along the Utah line to the point of commencement.

These are the boundaries of Nevada – battle-born child of the republic, thirty-sixth star of the American constellation. As are her boundaries, so are her varied physical

aspects within those boundaries. Three hundred miles north and south, and 250 miles cast and west, of an elevated plateau between the Sierra Nevada and the Rocky

Mountains, is the general description of Nevada, but what pen shall do justice to the wonderful details? The man who loves the wild in nature, who delights in contrasts,

and seeks strange sights, will not visit her soil in vain. He will behold a land of rugged mountains,

[318]

still bearing the marks of the volcanic fires by which they were upheaved from the chaotic gloom which stretched out before the morning ere God said, "Let there be light."

He will stand by the side of a hundred springs or geysers, ejecting boiling water impregnated with mineral, potent in the cure of diseases as the pool of Bethesda of old,

and as sulphurously and unpleasantly suggestive of a region not to be mentioned to ears polite as the most orthodox Puritan could desire. He will travel through lovely

valleys blossoming in emerald beauty, and, crossing a river, find himself in a region of awful sterility, blasted by the breath of the Almighty, with no drop of water to cool the

desert air, and no living thing to stir the stillness which has brooded there since the dawn of creation. He will enjoy a delicious climate, and an atmosphere balmy as the

breath of June, occasionally alternated by a rigor that renders the name of Nevada, or "snowy," not altogether inappropriate -- by snows which last until late in May, and

blasts that hurl the giant pines of the mountains in a demon waltz to the music of the shaking hills.

The new State, boisterous in patriotism, and exulting in a majority of nearly two to one for Abraham Lincoln, with a clause in her organic law declaring that "the paramount

allegiance of the citizen is due to the Federal Government," comes bursting into the Union without the decorous delay of long courtship that preceded the "sealing" of her

sisters. Five years ago and the State of Nevada was only Carson County in Western Utah, uninhabited except by a few Mormons at Genoa in Carson Valley, and hurried

through by the California bound emigrant as a sort of Valley of the Shadow of Death through which it was necessary to pass to reach the promised land. To many it was

a valley of death indeed, as the skeletons of men and cattle that line the banks of the Humboldt still testify. Silver was the vivifying power that caused this lotus flower of the

mountains to burst forth full-blown upon the national stem to which her war-crimsoned sisters are clinging. In 1859 silver was discovered upon a spot in the mountains east

of Carson Valley, where now the City of Virginia stands. A few hundred pioneers crossed the Sierras that season and hibernated in the hills through the winter. The following

year (1860) the value and permanent character of the silver-bearing quartz ledges was partially demonstrated and a considerable emigration attracted. In 1861 expensive

toll roads across the Sierras were completed, mills erected, machinery transported, and the foundations of Nevada, or, as it was then familiarly called, "Washoe,"

permanently laid. The developments already made proved that along the base of Mount Davidson, under the streets of the future metropolis of Silverland, for a distance of

two miles from Cedar Hill on the north to Gold Hill on the south, there meandered immense, and, in point of depth, seemingly inexhaustible veins of rich silver-bearing rock,

running parallel to each other, and called -- after the discoverer of silver -- by the generic name of "the Comstock Ledge." There was no good reason why these same veins

should not be discovered for miles north and south of their present points of boundary. There was no good reason why a hundred other "Comstocks" might not be found,

or why every quartz ledge might not be of equal richness. The busy era of adventure, enterprise, and toil was followed by the era of "wildcat." From October, 1862, until

March, 1864, speculation ran riot, and the Territory of Nevada was converted into one vast swindling stock exchange. The rich developments upon this famed Comstock

Ledge, the growing exports of bullion from the Esmeralda region, discovered in 1861, the glittering promise from quartz ledges discovered in Humboldt County, and the rich

assays of "chloride" rock from the Reese River country, whose mineral wealth was discovered in the autumn of 1862, all exaggerated tenfold, frenzied the public mind upon

the subject of silver mining, and a feverish gambling excitement usurped the places formerly occupied by legitimate and prudent adventure. Hundreds of companies with

capitals -- on paper -- of from $500,000 to $5,000,000 each, were formed every month in California and Nevada. Every merchant and merchant's clerk, every mechanic, every

laborer, every servant girl, in every city and village on the Pacific coast, was in possession of a pocketful of stock not inappropriately designated as "wild-cat." A grocery

importer in San Francisco complained that he could not get his business properly attended to, because his book-keeper and assistant were President and Secretary, and

his salesmen and porters Trustees of a flourishing mining company, and the necessities of the stock market deranged the due delivery of sugars and teas. Montgomery

Street, in San Francisco, and C Street in Virginia -- which had now become a city of 20,000 inhabitants -- were thronged from morning until night with crowds buying and

selling stock, chaffing each other, and exhibiting specimens of quarts. Three stock boards, with rooms magnificently furnished, were in full operation in San Francisco.

Sacramento, Marysville, and Stockton, each had their stock board. In Virginia City there were four, and transactions to the amount of hundreds of thousands of dollars

were often made in an hour. A report of a "rich strike," a report of a mine being "salted," an alleged discovery of the Comstock, a rumor that the Supreme Court would grant

an injunction, a rumor that the Supreme Court would raise an injunction -- any or all of such would affect the value of prominent stocks from 20 to 100 per cent. in a day. In

this whirl of mad excitement Virginia City most profited. Hotels, boarding-houses, stables, and hay-yards were filled to overflowing. In stages, in buggies, on horseback,

muleback, and on foot thousands flocked across the mountains to swell the excited throng. A few brought their families, and $100 in gold per month was demanded and

freely

[319]

paid for a cabin of four or five rooms, and three times that amount for a decent cottage. In Austin, Reese River district, the bubble was inflated to even a greater extent.

Men bought town lots for $400 a front foot in a spot where twelve months before only the cry of the coyote disturbed the primeval stillness. On these lots buildings were

erected with lumber purchased at an expense of $500 in gold per 1000 feet, and the building readily rented for a monthly sum equal to 10 per cent. of the cost of the

building and ground. Of every hundred who invested in mining stock ninety-nine never saw, or intended to see, or designed to work the mine. To sell out, to speculate, to

gamble was the object of all. What wonder that when the bubble burst, as it did late in the spring of 1864, the distrust and disgust was as wide-spread as the disaster it

brought. Gould and Curry tumbled from $6400 to $840 per foot; Ophir from $4000 to $400; other leading stocks in proportion; while the numerous "wild-cats," quoted at

from $20 to $200 per share, descended irrevocably to that sum which can only be designated by a cipher. All over the mining districts of Nevada may now be seen hundreds

of partially opened mines once of known and recognized value, but now utterly valueless, or with shares of only a nominal value in the stock market. The sound of the pick

is heard no more in their deserted galleries; their shafts are caved in or partially filled with water; their disheartened, disgusted owners will not even pay a small assessment

to preserve works already constructed from devastation and decay, and yet the mines are as rich as ever; the ledge is perhaps just beyond, waiting only the Midas touch of

patient industry to uncover its glittering deposit. Silver mining, like every other business, requires to be managed as a business and not as a speculation. The people of the

Pacific coast have discovered this by bitter experience, and the dark cloud of despair and hard times which settled upon Nevada after the wild-cat babble burst is slowly

beginning to fade away. The Mexican proverb, that "it takes a mine to work a mine," has become a truism; for when a quartz ledge promising richness is "struck," and

discovered to prospect well, the troubles of the discoverer are about to commence. To run a tunnel or sink a shaft, often blasted through solid rock four or five hundred feet,

will require six months' labor of five or six men. If water be struck, as is generally the case, expensive pumping machinery will be needed; then drifts and galleries must be

cut and timbered up for protection against caving, and all generally before pay ore can be profitably extracted. To open, drain, and thoroughly prospect a first-class silver

mine, with miners' wages at the present rates of $4 in specie per day, will cost from $50,000 to $100,000 in gold. Is it a marvel that Comstock, the discoverer of all this

wealth, is mining with indifferent success in the Boise country; that Gould, the locator of the great "Gould and Curry Mine," is cutting shingles for subsistence; and Chollar,

the locator of the Chollar Mine, now worth between $1,000,000 and $2,000,000, is prospecting still for "a pile?"

It is true that many silver mines, opened at a cost of $100,000, yield $1,000,000 in gold and silver each year, and pay annual dividends to their stockholders of over 100

per cent. upon their original cost, nevertheless considerable misapprehension exists concerning the profits of silver mining. Twenty per cent. of profit upon the gross value

of the bullion extracted is esteemed as very rich, and few mines will average as much. The Gould and Curry Mine, situated in Virginia District, produced during the autumn,

winter, and spring of 1863-'64 about three quarters of a million of dollars in bullion bars each month; the dividends to the stockholders during the same time were about

$200,000 per month. There are dozens of small claims yielding from $25,000 to $100,000 in bullion each month, and paying their owners a profit of from $1000 to $6000

per month. The effect of such a tax as was proposed at the last session of Congress of 5 per cent. upon the gross proceeds" would be to close most of such mines. Ore

has been found yielding $2000 in silver to the ton of quartz rock, but $100 per ton is very rich, and the great mass of the best claims yield on an average not over $40 to

$50 per ton. When it is remembered that the charge for milling or reducing rock is from $20 to $25 per ton, and that it costs from $5 to $15 per ton to excavate the quartz,

raise it to the surface, and haul it to the mill, it will readily be seen that the silver bars which generous Nevada poured into the treasury of the Sanitary Commission were

the result of a toilsome and expensive process, and not picked up by the way-side.

The character of the mining in Nevada, requiring a large outlay of capital before return, has produced the present system of incorporated companies. This system was

originally designed for the laudable purpose of concentrating the capital of many to undertake expensive works for which individual means would be totally inadequate;

but it has in many instances been widely perverted from the original design, and used as a vehicle for swindling speculative purposes. Brown and his four friends discover

and locate a quartz ledge, taking up five claims thereon of 200 feet each, with 200 feet extra for the discoverer. Labor enough is performed upon the ledge to comply with

mining laws and hold it for one, three, or six months. Forthwith a company is formed and incorporated. Brown is made President, Jones Secretary, and the other locators

Trustees. Beautifully engraved stock is placed in the market, and given away or sold for one, two, or five dollars a share. A small assessment of fifty cents or one dollar per

share is levied to pay the expenses of incorporation, and of commencing a shaft. Sometimes succeeding assessments of five, ten, and twenty-five dollars a share are levied,

and the development of the mine vigorously prosecuted; oftener, however, all work is suspended as soon as the original holders have succeeded

[320]

in getting rid of their "wild-cat" stock. In those cases -- few in proportion -- where heavy assessments have been paid and mines thoroughly opened, it would be safe to

estimate that from one-third to one-half of the money expended has been wasted in high salaries to officers, squandered in the erection of useless and expensive brick

offices and houses for superintendents, or misappropriated in unnecessary works. Litigation has also been a fruitful source of outgo and corruption. A mine never becomes

valuable in Nevada without starting half a dozen litigious claimants after it. Companies are incorporated to prosecute "fighting titles." If a compromise be not effected, then

heavy fees to counsel, large sums to scientific "experts," enormous bribes to witnesses and jurors, and, as has been often asserted, to judges, follows, until the

stockholder is fain to imagine his silver mine a species of incorporeal Oliver Twist, continually "asking for more," and yielding no return. It is an evidence of the real wealth

of Nevada, that, in despite of half of the ore-yielding claims being tied up by injunction, pending a determination of title -- in despite of enormous expenditures and waste --

in despite of the flocks of "wild-cats" and the thousands of "honest miners," whose object is to sell and not work their claims, the yield of bullion has continued to steadily

increase. A new system of procuring capital to work silver mines has recently been devised, and meets with some success, as indeed it should, because it obviates the

objection which many entertained against buying into a company whose trustees might at any time perform the not uncommon antic of levying a heavy assessment,

depreciating or "bearing" the stock in the market, and as "freezing out" the poor holder. The new system is to make a liberal estimate of the actual expense of opening

a mine and placing it in dividend-paying order; to issue full paid stock upon this basis, and sell it outright for a sum sufficient to meet the required expenditure, the owners

of the ledge receiving a portion of such stock in payment for their interest. Suppose that it will cost $100,000 to open a mine, then stock to the amount of $200,000 may

be issued, one half paid to the owners of the ledge for their title and the other half sold at par. With the money obtained from the sale the mine is placed in paying order,

and all parties draw large dividends. This process is decidedly preferable to the present plan of continuous assessment and "selling out" of delinquent holders. If the mine

so developed be of even average value it can scarcely fail to return from 10 to 20 per cent. per month to the investor, and silver mines are unlike gold mines in that they are

inexhaustible, and may be worked for generations when once opened.

Nevada is still largely in debt to California -- indeed how could it be otherwise? The freight alone on goods, machinery, etc., hauled across the Sierra mountains during the

year 1863 amounted to something more than $13,000,000 in gold. It would be safe to estimate that the original cost in California of the articles for which this freight was

paid was not less than $27,000,000 in gold; making $40,000,000 of imports, while the yield of silver and gold for that year was less than $20,000,000. To this $40,000,000

must be added the large sums of ready money sent over for investment in buildings, mines, mills, etc., and it will readily be seen that the people of Nevada are still greatly

in debt; although 1864 has produced a larger yield of bullion and the amount of articles purchased in California has greatly decreased, both because of the diminished

demand for heavy castings of machinery, and the increase of home agricultural and mechanical productions. Nevada will pour from $25,000,000 to $80,000,000 of silver into

the treasury of the world during the year 1865; and when the completion of the Central Pacific Railroad, to a point near Virginia City, shall afford facilities for cheap

transportation, which will justify forwarding the lower grade of silver ores to the Sierra mountains for redaction, the present annual yield of silver will be trebled. There are

hundreds of mines in the mining districts within five to twenty miles of the Carson River now lying idle and unworked, which are capable of yielding many million tons of ore

that will produce 20 or 25 ounces of silver to the ton. Such mines are now valueless because -- as has been before stated in this article -- the charge for reduction at the

mills is not less than from $20 to $25 in gold per ton. In the Sierras, thirty to fifty miles distant, where wood and water is abundant, the same rock might be profitably worked

for from $5 to $10 per ton; and a railroad could drive a most lucrative trade by transporting it for $5 per ton.

If Nature has denied to Nevada the fertile beauty, the smiling prairies, the green verdure, and the wooded hills of more favored States, she has amply compensated for the

deficiency by most munificent and peculiar endowments in other directions. Silver and gold will not be the only exports of this State when the Pacific Railroad shall have

hewed for her a highway to the rest of the world. Several companies are now supplying her people with fine salt of the very purest character found in an immense bed,

hundreds of acres in extent, about sixty miles from Virginia. This salt is very fine and pure, perfectly crystallized, and needs no other preparation for market than being

shoveled into sacks. The value of this inexhaustible supply may be estimated when it is known that salt is used in all quartz mills, and is an article of prime necessity

in the reduction of silver ores by the present process. Immense beds of natural potash, sulphur, and alum, perfectly pure and ready for use, have been discovered in

various portions of Central Nevada; all these are of course valueless at present, but must some time become of great value. Bituminous coal of a very fair character has

recently been found in several localities, and there is no doubt of the existence of large beds of this indispensable article for fuel and manufacturing purposes.

[321]

Nevada, although peculiarly a mineral country, is by no menus destitute of agricultural lands. The business of farming, however, must for many years be limited in extent,

inasmuch as her great distance from navigable streams connecting with the ocean, her isolation behind mountain barriers, and her utter destitution of railroad facilities

forces her farmers to rely exclusively upon the mining population for a market. Washoe Valley, Carson Valley, and the Truckee meadows, all upon the western border of

the State, already produce grasses, cereals, and vegetables enough for the mining communities adjacent, and have still many thousand acres uncultivated within their

borders. The Reese River country upon the eastern border of the State, Humboldt to the north and Esmeralda to the south, also contain many fertile valleys. As there are

necessarily large quantities of barley and hay used for the vast number of animals employed in transportation of freight across the Sierra Mountains, and as the long road

across these same mountains acts in the nature of a protective tariff, the farmers have hitherto been among the most prosperous members of the community. Prosperity

is not difficult to the owner of natural meadows yielding from one and a half to two tons of hay per acre, selling on the ground for from $40 to $50 in gold per ton, with

corresponding prices for barley, potatoes, and all articles of dairy or farm produce. The country being new there has as yet been but little attention paid to orchard gardening.

The altitude even of the lowest valleys being some 4000 feet above the sea, and the seasons late, it is not probable that Pomona will ever smile upon Nevada as she has

beamed over all the broad valleys of the Sacramento and the San Joaquin; but the apple and the pear can certainly be most profitably cultivated, the hardier varieties of

peach can be made to grow without difficulty, while the volcanic nature of the soil upon the mountains renders it peculiarly adapted to the growth of the grape. In Nevada

as in California artificial irrigation must be resorted to in order to raise crops, and here again a difficulty in the path of agricultural development presents itself. The great

mass of the water collected in the Sierras pours down their western slope, forming springs and rivulets in abundance, which, in their progress toward the Pacific ocean,

are carried into every town by the great flumes or ditches constructed for mining purposes until every mining village in California is now embowered in shrubbery. In Nevada,

however, comparatively but little water descends from the Sierras, and the mining being almost exclusively quartz mining, there are none of these life-giving, grass and

flower-bringing "flumes." In Virginia City, for instance, a town of 20,000 inhabitants, all the water possible to collect is needed for other purposes than irrigation, and there

are not fifty shrubs or a hundred square feet of grass in the entire city. Artesian wells or an aqueduct from Lake Tahoe, thirty miles distant, will probably finally furnish the

means of correcting the unsightly appearance of Nevada's chief city.

Virginia, being 6400 feet above the sea level, is literally "a city set upon a hill whose light can not be

hid." "Croppings," or surface developments of quartz ledges, were discovered running along the side of Mount Davidson about 1500 feet below its summit, and from 500

to 800 feet above its base. Here Virginia sprang into being like a mushroom, but has gradually changed its fungous character of a mining camp, until it has become in

four years a thriving city of brick and stone edifices, containing more than 20,000 inhabitants, with theatres, churches, public halls, three daily papers, aldermen, city

indebtedness, and other public improvements. Gold Hill, adjoining Virginia to the south at the head of a cañon running down to the Carson River, contains from 5000 to

6000 inhabitants, and boasts of its daily paper. Austin in Lander County -- Reese River District -- and Aurora in Esmeralda, distant respectively 180 miles east, and 120

miles south of Virginia, are each of about 5000 inhabitants. Carson City, the State capital, situated in a valley at the base of the eastern slope of the Sierras, contains

2500 to 8000 inhabitants, while Dayton, Washoe City, Star City, Unionville, and Silver City have from 1000 to 2500 each. Many families reside in all these towns, and

Nevada is changing very much for the better in all her social characteristics. In 1862 a distinguished divine, who visited "the land of sage-brush and silver," and examined

the great Ophir mine and the numerous small excavations resembling those dug by gophers and called mines by courtesy or in ridicule, said, on his return to California,

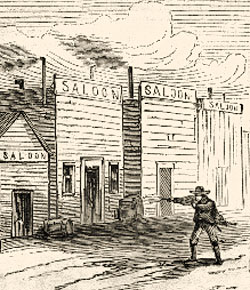

that "Washoe" was a land of "Ophir holes, gopher holes, and loafer holes." The latter have not entirely departed; but the halcyon days of the desperadoes and cutthroat

gamblers have gone, it is to be hoped, forever. In 1860 and 1861 the refuse ruffianism of California flocked over to the new Dorado. The sound of the pistol was almost as

frequent upon the streets of Virginia as the clink of silver from a hundred gambling-hells that lined her principal streets. "A man or two for breakfast," was the staple; and

the first inquiry of the morning made by the sober merchant or the tired sojourner to the man about town was, "Who was killed last night?" The hard times which succeeded

the financial crash of the spring of 1864 drove this undesirable class of citizens to "fresh fields and pastures new." Virginia is now orderly and well governed, while an increase

of churches and schools tells the talc of growing civilizing tendencies.

In 1860 a war broke out between the whites then in Nevada and the Pahutah or Piute Indians. Parties of miners out on prospecting expeditions were attacked by these

savages, who are a brave and warlike tribe, very unlike the miserable Diggers of California. Many settlers, miners, and savages were killed, and an expedition from Virginia

of a company of volunteers resulted in the defeat and almost entire

[322]

destruction of the company by the Piutes under Winnemucca. Peace was soon after made; and to-day dozens of these savages may be seen upon the streets of Virginia

splitting cord-wood and packing water for food and clothing, or seated in the street, playing cards for half dollars in emulation of their white instructors.

In the winter of 1860-'61 Nevada was organized as a Territory by Act of Congress, and James W. Nye, of New York, appointed Governor. The first Territorial Legislature met

at Carson City in November, 1861, and enacted a code of laws for the government of the Territory. Population continued to rapidly increase, and the second Territorial

Legislature in the winter of 1862-'63 passed an act providing for an election of Delegates to a Convention to frame a State Constitution in case the people should vote for

calling such Convention. They did so vote almost unanimously in September, 1863, and the first Constitutional Convention assembled at Carson City in November of that

year. Some six weeks were consumed in framing a Constitution, which was submitted to the people on the 19th January, 1864, and refused ratification by a vote of about

five to one. The causes of its rejection were manifold. The Democracy opposed it with their party organization because of a clause in the Bill of Rights declaring "that the

paramount allegiance of the citizen is due to the Federal Government." The Union men opposed it both because a most unacceptable ticket of State officers had been

nominated, and because of a disbelief in the ability of the people to support the expensive machinery of a State Government. Perhaps the greatest source of opposition to

it, however, originated in the fact that the Constitution as framed contained a clause declaring specifically that mines and mining property should be taxed equally with all

other property. This was an entirely different theory from that which prevailed in California, where mines have always been exempted from taxation, and was construed by

the great body of the miners to mean, not that the ore taken from the mine should be taxed, but that the right to search for a mine, the hole in the ground, the prospecting

shaft, the expectation of a rich quartz vein, the substance of silver hoped for, the evidence of gold unseen, should be taxed. The miners, therefore, went bodily against the

Constitution. In March, 1864, Congress passed an Act to enable the people of Nevada to form a State Government, wisely providing therein for an election of Delegates to

a Constitutional Convention and a day certain for holding the Convention, else might the disgusted and State-weary people have paid no attention to the opportunity of

obtaining sovereignty. As it was, a sickly sort of election was held in June, when not one-fourth of the popular vote was polled, and in July the members of the second

Constitutional Convention assembled in Carson City, with every body laughing at them for laboring to form a State Constitution which was "certain to be rejected," and

none so poor to do them reverence. A legislative chamber, or court-room, being empty, they were allowed to take possession of it, and the Territorial Secretary donated

them a very few quires of paper. A pony purse was made up among the members to buy candles, an obliging saloon-keeper was decoyed by promises of future legislative

payment to act as Sergeant-at-arms, and the Convention commenced its deliberations. The papers throughout Nevada generally ridiculed the proceedings, and advised

the members to go home; but they persevered amidst discouragements, and in three weeks the present excellent Constitution was produced. The rocks which wrecked

its predecessor were carefully avoided. Mines were especially exempted from all taxation except upon proceeds; the rate of taxation on property was restricted for the

first three years to one per cent.; the salaries of all public officers limited, and admirable checks placed upon public expenditure. The new Constitution grew in popularity

from the hour of its birth. Miners favored it because only the proceeds of the mines could be taxed. Merchants favored it because a State organization would enable them

to enjoy the benefits of a specific-contract or gold-currency act. Attorneys favored it because the Territorial judicial system was so entirely inadequate to the necessities

of litigation, and the Territorial judges so utterly odious to the people, that more courts and new judges became a prime necessity, unobtainable except at the price of

Statehood. Politicians favored it because of the many State offices to be striven for. Last, but not least, the great loyal heart of Nevada was fired by patriotic appeals to

add another star to the banner, and exhibit to the world a renewed confidence in republican government, even while the field of azure which bears our national symbols was

trembling beneath the vibrations of war.

And thus a constitution of State government, with a "paramount allegiance clause," but slightly modified from the first Constitution, was adopted in September, in a time

of general financial depression, with a unanimity greater than that which characterized the rejection of its predecessor in a time of general prosperity and excitement.

We have given in this hasty sketch an imperfect outline of the political, financial, and social history of Nevada. So fruitful of events has been the life of the young State that

a detailed history of men and things would occupy volumes instead of pages. The future of Nevada presents the outlines of a glowing picture, on which we might love to

dwell but that we are dealing with facts and not fancies. To the emigrant, bringing with him either a small capital in money, or the wealth of honest industry contained in a

pair of strong, willing arms, no more certain opportunity can present itself for the speedy acquisition of a competency than settlement within her borders. Whether he

engage in agriculture or mining, he can not fail. Unlike California, unlike any gold-bearing country

[323]

in the world, silver mines are inexhaustible, and, as a rule, grow richer as they descend into the earth. Not one in a hundred of the silver-bearing quartz veins of Nevada

are worked or even prospected. The production of the precious metals is yet in its infancy, while -- with numberless lodes of copper and iron -- production of the baser

metals has not yet been attempted. When science shall devise some process to extract the gold and silver which now is wasted in reduction; when railroads convey

ores to the vicinage of abundant supplies of fuel and waterpower in the Sierras; when this new State shall furnish yearly from its bowels a sum great enough to control

the exchanges of the world, and cause even the great national debt which this war has evoked to melt before the silver current as icebergs dwindle in the warm flow of the

Gulf stream -- then shall the citizen of Nevada, pointing to her patriotic motto of "All for our Country," look back upon the days of territorial immaturity and pupilage, and

of early statehood, and bless the pioneers who created an empire in the wilderness, and laid the foundations of a mighty commonwealth upon the summits of sterile hills.

Note: The illustrations are from pages 268-69 of the April 24, 1869 Harper's Weekly.

|